I am often asked, with all our home-steady proclivities at Sap Bush Hollow, if we have a family cow. These days, I readily exclaim “ABSOLUTELY NOT!” much to the consternation of dairy romantics. While a milk cow is definitely an enrichment for some families, it turned out it wasn’t ideal for us….This post originally ran in August, 2010. Trill is no longer with us, but she is most definitely here in memory. I am still at work on my new manuscript, and anticipate a return to regularly scheduled programming some time in May.

A tragi-comedy of epic proportions….

If you ask Mom, she’ll say it was my idea to get the family cow. In truth, it was her idea. I only ran the numbers and showed them to Dad, arguing that we couldn’t afford not to bring a dairy cow into our grassfed livestock herd. Mom is pretty much the business manager on the farm. Dad manages the livestock. My second-born, Ula, was spitting up on my shoulder when I presented the case to him.

“And who is going to help me milk this cow?” he asked. Most of my farm hours were spent selling steaks, linking sausages and wrapping lamb chops; since my teenage years showing sheep at the fair, I’d handled the animals very little; I was more confident jostling babies and hefting meat. But I’d asked around to find out what kind of time it took to hand-milk a cow. Twenty minutes twice a day, I’d learned. It seemed doable. “I will.”

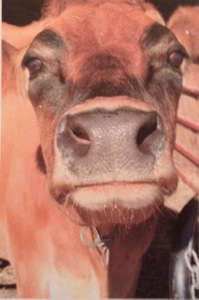

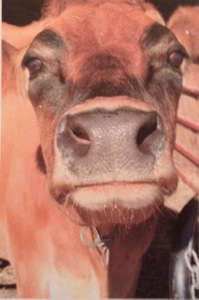

A few weeks later, Bob and I came home from the farmer’s market to find Saoirse dancing in the driveway. “Mommy! Mommy! Pop Pop bought a cow, and her name is Trill!” There in our holding pen was a frightened five-year-old Jersey, culled from her herd because, the farmer who sold her to us explained, he thought her teats were so nice and small, they’d be good for hand-milking. (Important side note: no dairy farmer sells a bred, lactating Jersey cow without a good reason.)

I kept my promise to Dad, and went out to help him tie her up. He sat down to do the first milking, and I massaged her sides and scratched behind her ears. Frantic from her journey on a truck and un-used to hand-milking, she was having none of it. By the week’s end, our arms were covered in abrasions from her kicks, our fingers and wrists felt arthritic from squeezing her teats, and I was beginning to walk with a stoop every time I stood up from underneath her.

I figured out that if I sang her lullabies, she’d let her milk down, and reward us with perhaps two measly cups at each milking. Dad figured out that she would come in out of the pasture for milking only if we bribed her with grain, ending the “grassfed dairy cow” idea. We discovered that she had an extra hole in one of her teats, (probably the reason the dairy farmer sold her) that required us to milk it normally, squirting down, then to turn the teat and milk it again sideways to thoroughly clean her out. If we didn’t do that, she developed mastitis. We also learned that if anyone other than Dad or myself milked her, she developed mastitis. If we altered her milking time slightly, she developed mastitis. If she was coming into heat, she’d develop mastitis. I looked up mastitis in our Mercks veterinary manual. It said that generally, if a dairy cow developed mastitis more than three times in one year, she should be culled from the herd and sent for slaughter. Instead, the dairy farmer sold her to us. Dad and I wondered if we should ship her for slaughter.

But, we told each other, she had such a nice personality. If we brought her grain, she would come to us, unlike any of the other livestock. Once she was tied in the barn, she’d rub her forehead against my jeans, and enjoyed it when I worked my fingers up over her poll and behind her ears.

In hindsight, those were her only nice attributes. Dad and I learned to wear hats at all times during milking, because once we were under her, she took great pleasure in whipping our faces with her tail. We had to milk quickly, because once she finished her grain, she’d begin kicking us as well; causing flecks of manure to fly off her hooves and contaminate our milking pots, forcing us to dump our hard-earned harvest. Eventually I developed a knack for sensing the slight ripple in her muscles that preceded each punt, enabling me to swoop the milking pot (and myself) out from under her and turn sideways just in time to avoid her hooves.

Her best trick, however, was revealed once the colder months came on. As the days grew crisp, we discovered Trill was an udder-dunker. When she bedded down for the night, she’d find her freshest, softest, warmest cow plop in which to nestle in her udder, leaving us a delightful mess of caked-on manure to remove before each milking. Perhaps the estimate that hand-milking a dairy cow takes 20 minutes was accurate. But prepping the milking equipment, finding the cow, cleaning her udder and interrupting milking to endure her kicks adds a good 60 minutes to the job.

It wasn’t long before Trill became the source of family arguments. Mom would call me on the phone to complain that I wasn’t doing my fair share of milking. With a breast-fed baby on my own teats, I argued back that we’d gotten the cow too soon, and they needed to be merciful with my own lactation requirements. Dad would grouse and complain that the labor on the farm was too much. I would run down early in the mornings, without having breakfast with my kids, to do the milking, leaving Bob to grapple un-aided with two little girls who wanted their mommy. I would cry because I was spending all my time at the farm and missing my girls. They’d cry because they missed me. I’d get exhausted, insist on having a few days home with the kids, and Mom would call again on the phone to complain, starting the cycle all over. Bob was the only one who kept a sensible head through the whole ordeal.

“Get rid of the damn cow.”

At first, I ignored him. Getting rid of the cow was just ridiculous.

By that time, we were now enjoying a gallon of milk twice per day. I was making kefir and yogurt. Mom was making butter. But Dad and I were gaining more from it. When it was my turn to milk, if Trill was in a good mood, I’d rest my cheek along her haunch, breathe in her sweet smell, and watch the morning sunlight rise over the maple trees on our side hill. I’d feel my heart rate slow and my worries dissipate as I matched my pace to the cow. Dad would almost always meander over to offer her some pets, and we’d talk. We’d talk about family troubles, make jokes, and figure out how to organize the week ahead of us. I’d tell him about my writing projects, and he’d tell me about his reading. I began asking questions about managing the livestock. When do the sheep get moved to the next pasture? Why are we keeping the calves in that field? What is the gestation period for a sheep? Why do we breed in December? How do I work those fencing panels in the front field? Why are the pigs acting that way?

Until we got Trill, I’d wanted to insert myself more into the livestock management part of the business. My inheritance is Sap Bush Hollow Farm, and I live in fear that something will happen to my parents, and I won’t know enough to take it over. Our days are so busy seeing to our specialized tasks – Bob and I selling meat and taking care of our girls, Mom handling phone calls and paying bills, Dad making all the farm management decisions, that none of us knows how to fill in for whoever may be missing. As the person who is next in line to manage the land, that is a scary feeling. Trill was just one animal on the farm, but I was learning how to handle her effectively. And while I was handling her, I was learning about how Dad manages the farm.

Then, last August, for the first time, Dad and I left the farm at the same time with Mom and the girls to attend a family wedding. Bob and our intern stayed to milk Trill and handle the chores. We received a phone call as soon as we arrived at our destination. Now an aging dairy cow, Trill’s udder had been sagging under the weight of the milk. She had been lying down in the pasture, and when she stood up, she accidentally stepped on it, and tore one of her teats very badly. Bob had to call in the vet to stitch her up. We returned two days later facing a big bill and an angry cow. She whalloped Dad’s knee with her rear hooves, injuring him; and nearly kicked my head several times. I became too afraid to milk her.

Our family feud resumed. By September, Mom was calling again to complain that Dad was overworked. But this time I listened to Bob. Rather than making excuses or running down to milk, I remained firm. “Trill has to go. Put her on the truck.”

“Your father won’t do it.”

For three years, even though I had to endure her abuse, I’d looked at Trill as my friend. Now I remembered that some of the best pot roast I’d ever had came from a 10 year old dairy cow. I went down to the farm for the next milking.

“Dad. She has to go.”

He grunted as she kicked his now bad knee and said nothing. “Dad. She isn’t taking her breeding. She’s not pregnant. And she’ll taste fantastic.” Trill whipped his face with her tail. He still didn’t speak. “Your own rule on this farm is that if an animal is dangerous, it’s got to go.” She kicked him again. He yelped in pain, then kept milking. “You’re a co-dependent to damned cow!”

I stormed off. I waited in the kitchen until he came in. He handed me the milk, and as I poured it through the filter, I resumed my argument. He and Mom were scheduled to go away on vacation in October. Bob and I were to stay at the farm with the girls. I was to do the milking.

“Dad. I can’t milk her anymore. She’ll kick my head in. Clint (our butcher) and I can process her while you’re gone. You won’t have to have anything to do with it.”

“I’ll think about it.”

I went ahead and made plans with Clint. A few days later, Mom called. “Your father had Trill bred again” Outraged, I went back down to the farm.

I found him hunched once more at the altar of his abuser. I said nothing. She was standing quietly, allowing him to milk her. Finally he stood up from the stool.

“You try.”

I sat down beside my former friend. I reached out to wrap my hand around her teat, and her flying hoof narrowly missed my temple. Adrenalin raced across my taste buds.

“I can’t do it, Dad!”

“Yes you can.”

I tried again. She caught my arm this time, scraping it. Tears of anger, pain and fear streamed down my face. I remembered why I wasn’t the livestock manager. I’m too small to handle large animals. Too weak. I don’t have skills. This is a man’s position on the farm. Not mine.

“You need to be the boss, Shannon. She knows you’re afraid and she’s taking advantage.”

With that, anger superseded my pain and fear. I threw the milking pot down, allowing the milk to spill out over the barn floor. I put my right hand in her haunch and held firm, and grasped her teat with my left. “Cut it out!” I yelled at Trill. “I’m taking your milk, whether I get any or not!” Holding her firmly, I milked her out onto the barn floor, allowing every last drip to run over the hay she stood on. I felt her muscles twitching under my arm in her unsuccessful attempts to kick me away. I didn’t release my grip. Then, slowly, she relaxed. I held her in place and continued to milk. By the end of our session, she was docile (aside from her customary tail whips), and I had gone back to collecting the milk.

“The animals respond when they know they have a boss,” was all Dad said. He and Mom went away on vacation. I milked Trill. When it got cold enough for her to start dunking her udder, we smartened up and dried her off.

Clint and I started off the processing season this year by making several hundred pounds of pork sausage. I went in to the house early in the morning to grab the spices. Dad was sitting in his rocking chair. “Shannon, what time will you be finished today?”

“I don’t know, Dad. It’s sausage day. We go ‘til we’re done.”

“You need to be finished by 5:30. There’s a new mobile slaughter house up in Stamford. Trill needs to be there by 6pm.” I nodded and tried to remain stoic.

“She’s not pregnant?”

“She aborted.”

I forgot about the prospect of tasty beef and ran out to the barn and burst into tears. Saoirse came to find me. I told her the news, explaining that it was the right thing to do; that Trill was too old to be our milk cow any longer. We had a good cry together.

At lunch we received a phone call. Since Trill would be the inaugural cow in the nation’s first mobile slaughterhouse, a long-needed advancement for small scale livestock farmers, the New York Times would be there to photograph her as she came off the truck — A sort of macabre ribbon-cutting ceremony. It seemed fitting that she was destined for greatness in some way.

If you’ll refer to the New York Times story titled “A Movable Beast,”from May 17th, by Christine Mulhke, you will notice that a cow is walking off a truck and up a ramp, flanked by a father and son butcher.

That cow is not Trill. At 5 pm the day that photo was to be taken, Trill was in the holding pen, chewing her cud contentedly, expecting a few handfuls of grain for agreeing to come in out of the pasture. Dad was in the house sobbing. I was muttering quiet prayers while stirring sausage spices. And Mom was putting her foot down. “Damn it Jim! We can afford to keep a damn cow!”

In the end, it was Mom who called the slaughter house and told them to forget it. She decided that we were wealthy enough to have a permanent pet Jersey cow. Dad hung his head with embarrassment as he scuttled out of the house to let Trill out of the holding pen and send her up to the night pasture, never to be bred-back, and never to be slaughtered. Saoirse and I jumped up and down and cheered. Once a family cow, always a family cow.

Chores go a lot faster, now that we don’t have to milk Trill. I catch the pigs, monitor the cattle, scramble after the lambs, help evaluate body conditioning, and assist in moving the chickens. Most of the time, Saoirse works beside me, and Ula comes along for the ride. They share my growing confidence with the animals. I’m learning more about livestock health and pasture management, and asking more questions than ever, even though there’s no cow to stand around to help start the conversation.

The other day, Dad suggested that maybe we should try breeding Trill back again. Mom and I both quickly and adamantly voted against the idea. Milking Trill has been a lot like beating our heads against the wall as a headache remedy, I argued. One only does it because it feels good to stop. And she’s very much enjoying her permanent retirement. Besides, I think we’ve milked her for all she’s worth.

This post was written by Shannon Hayes, whose blog, RadicalHomemakers.com and GrassfedCooking.com, is supported by the sale of her books, farm products and handcrafts. If you like the writing and want to support this creative work, please consider visiting the blog’s farm and book store.

To view Ula’s Greeting Cards and support Saoirse and Ula’s (Shannon and Bob’s kids) entrepreneurial ventures, click here.

Feel free to click on any of the links below to learn about Shannon’s other book titles:

Hi Shannon, I will often take one of our more tame Hereford beef cows and milk her once or twice a day with pretty good results. Keeping her calf with her makes it less demanding , and once the calf gets bigger you can stop and let it have all the milk. I have the same results with our goats. I would like to eventually have a grass fed dairy Cheese making business . We are fortunate to have a nearby dairy farm that has 100 Grassfed, organic jersey dairy cows where we buy 2 or 3 gallons of raw milk/ week.

Hope all is well. Charlie Huebner

I’m so glad you shared your experience. Folks who present only the rosy side of any endeavor don’t make it easy to other newcomers. When we launched into our family cow experience we thought we’d handle things a certain way (no electric fence, hand milking, no stanchion, never a drop of grain). And we learned. The animals themselves are the best teacher. Our 3 year old Guernsey arrived as a creature of habit. Without an electric fence she made a hobby of pushing in fence wires. Without a stanchion she decided to turn around and leave during milking. Once her barn and pastures were set up the way she was used to it became much easier (except for hauling poo, that never gets easier). She seemed to feel comforted by a stanchion and small milking machine (eventually we ended up hand milking, that’s another story), with a handful of grain as her reward for coming in to be milked.

She’s now 16 years old, nursing a calf, and a defining personality on our little farm. Here’s a tale of Isabelle’s life with us: http://www.culinate.com/search/q,vt=top,q=isabelle/260442

I’m the only person on our farm who has ever milked our family cow, a Jersey named Daisy. Like your Trill, Daisy also has a less-than-ideal udder with one barely functional teat. It’s difficult to get a dairyman to let go of an ideal cow. In 2006, a friend of ours, at that time a novice beef producer, bought Daisy and a bull calf fresh off the bottle from a dairyman in Wisconsin and brought them to Kentucky.

I have had Daisy since she was a first-calf heifer in fall 2008, with a Jersey heifer calf at side. For about nine months prior to Daisy’s arrival, I wanted fresh milk so much that I had tried milking two of our better-milking Hereford cows. Milking beef cows made me appreciate the special talents of this little Jersey that much more. Although I had some initial experiences similar to yours, the quality and quantity and ease of milking were so much better compared to the Herefords, that I never though twice about keeping Daisy.

I do have a very different method of managing our family cow than many other folks. I allow her to raise her calf, which allows both Daisy and her caretaker to be far more relaxed. Some days, if I have enough milk on hand or if I need to be away from the farm at milking time, I don’t milk Daisy at all, allowing her calf to take over milking duties. I milk her once each day when I need milk. We allow our Hereford bulls to breed her naturally.

She is, of course, an excellent mother. Twice in her lifetime so far, she has raised high-quality red veal bull calves that weighed as much as she does by weaning. Her three half-breed heifer calves have made good beef-producing cows. If I need to be off the farm, her calf stays with her while I’m gone, assuring that she will not get mastitis from being under-milked. (Apple cider vinegar is the best treatment I have found if she begins to show any sign of mastitis.)

I have always had animals–cats, dogs, horses, birds, beef cattle, bottle calves and more. Never in a half-century of animal husbandry have I enjoyed the company of an animal as much as I have enjoyed the company of this little doe-eyed Jersey. Her grass-fed milk has vastly improved my health and helped heal my son’s ulcerative colitis. In return, she gets the best perennial ryegrass and clover we have during the green season, alfalfa hay and soyhull pellets while I am milking her, and a human companion who sees to her needs and gives her an appreciative scratch behind the poll each time we meet.

Although I used to milk Jersey cows (with a milking machine), and although I LOVE Jerseys, I much prefer hand milking my three goats! They don’t have tails to slap my face, they are small enough to not be dangerous to me, and they make me laugh with their silly personalities! Thanks for sharing this blog with us!

Shannon–and Laura Grace, also–I enjoyed reading your articles. I have Irish Dexters and find them wonderful animals. My first adult milking experience happened because I decided to milk one of my cows at her next year’s freshening…but–idiotically–I made no preparation. Cow calved on a Monday. I called a handmilker for a refresher course and on Tuesday we got the cow and calf into the barn. I put hay in the stanchion where my dad had milked our Jersey family cow so many years before with me at his side (why I said “refresher” course). Cow started munching. My cow, Heiress, would turn her head around from her eating each time I tried to close the stanchion headboard. So no milking that Tues morning. However, after my friend went home and while the cow was still eating, I decided to touch the cow where the stanchion board would connect and then all over, working my way around her and down to her udder. She was (is) one amazing animal. By Wed eve, I was milking that cow with no restraints on her (never did close the stanchion boards). Never a kick. Don’t now remember any trouble with the tail. I did not milk her for her full lactation and never did take the calf off, but I got enough milk for my little need and got a new sense of appreciation for Heiress. She is one calm cow. I know that now because I have milked others of my cows for varying lengths of time, with not always as easy an experience. Heiress is almost 16. When spring springs and the sun is warm and the cows are lying around enjoying the sunshine and I am walking among them, I sometimes sit down in the new grass beside Heiress and lean back on her and enjoy the sunshine too.

Did I fail to say that at the time I decided to milk Heiress I had not TOUCHED my Dexters and raised them instead as a beef herd? That’s an important detail–that she hadn’t been touched before!

That’s a beautifully written and amazingly frank view of your dairy experience and as someone on the very cusp of picking up a jersey from a nearby dairy to bring home to our farm, I’m grateful for it.

I have the added advantage/disadvantage of this family farm I’m on being a retired dairy, and my Dad a retired dairyman. He’s pretty unambiguous about his views on me hand milking at all, and looks like we might invest in a milking machine at the same time as the cow, not that that’s going to solve much, perhaps.

Your writing absolutely rocks, I loved this post. Thank you.

xxx