Wow. Folks get riled up when they talk about food prices when buying direct from farmers. And yet, for all the understanding the local food movement seems to have about fair wages for farmers, based on your comments these past weeks, it seems like we all have some war stories to tell In this three part series on pricing we spent the first part looking at how the complaining customer is just par for the course and learning how not to take it personally. In Part II, we heard my story about Agnes & The Cloak of Shame…And discovered how it isn’t the criticizing customers who make us feel bad, it is our own sense of shame stands in the way of us asking for what we need. In the final part, we’ll be looking at a section from my newest book, Redefining Rich, and exploring the art of pricing, and how it can improve more than your business’ bottom line…

There is no sale without a price. My family farm commemorated its fortieth year of business in 2019, and in my lifetime here, I’ve learned a few good lessons about pricing.

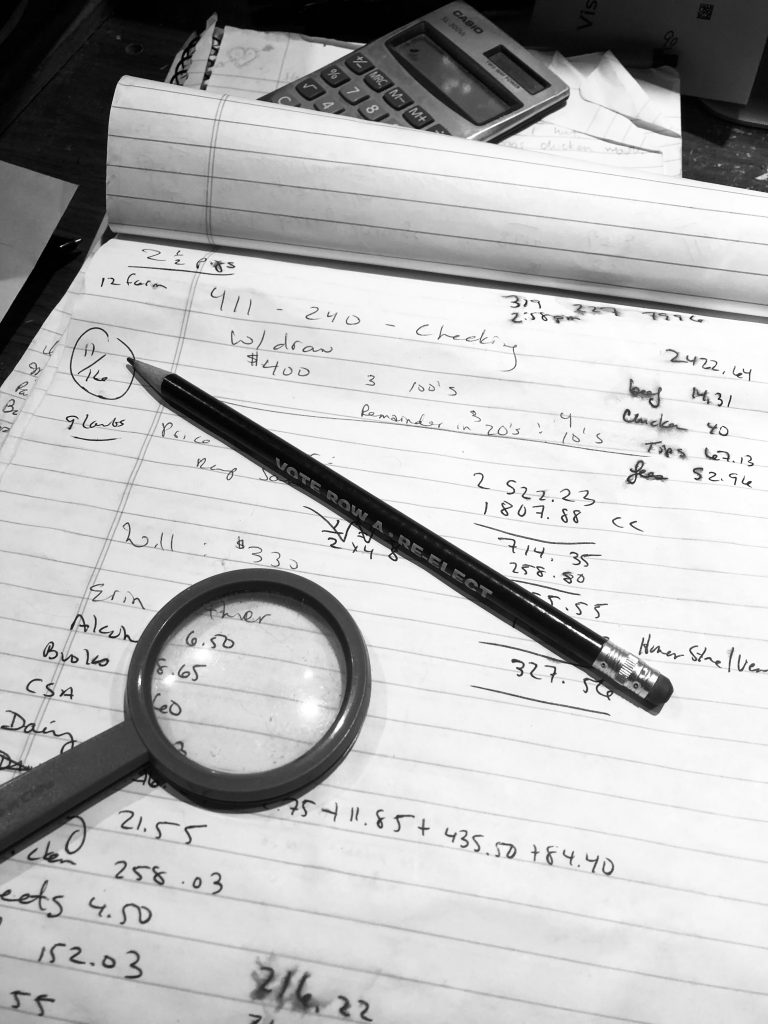

Pricing is where math meets art

I have price calculation sheets, recorded notes about the cost of live- stock, butcher fees, transportation charges. I have records, spreadsheets, and databases about woolen mill fees, truck mileage, the wholesale price of cooking ingredients, and cost per unit generated. For services like speaking and writing, I have calculations on the number of research hours required to complete a project, on actual preparation and travel time, on what comparable service providers are charging. I have scoured the web and attended classes to learn formulas about markup and return to equity. I periodically peruse national pricing of similar products. All of these things tell me one thing: a minimum typical average price. The rest of pricing is more of an art and less of a science. Our weekly prix fixe specials at the café sell for little more than cost; offering them is our effort to make a full, balanced, nutritionally dense meal available to our low-income community for as little as possible. It is our way of using

up the cuts that won’t sell well through the other retail channels and of creating good advertising for the café. But our à la carte menu items have a full markup. Our retail meats have little more than a 5 to 10 percent margin; our value-added soaps and salves have a full markup. Our goal is to strike an average where we all get a decent compensation package and the business sees a 5 to 10 percent return to equity at the end of the year. Once we understand the hard figures, the rest of our pricing decisions are purely qualitative, decided through family debates, consideration of community needs, and observations about what the market can bear . . . and then accepting the inevitability of change.

Some prices get moved up. Some get moved down. The greatest favor I’ve done for myself in the pricing department is to create a protocol for making updates. I noticed that our prices were falling out-of-date because it was too much bother for me to change them. To make the burden easier, I created a protocol that I can follow every time an adjustment is needed; it’s a step-by-step checklist that includes updating the point-of-sale software, updating the website, printing new price sheets, notifying our other retail partners, and physically changing the postings on the displays. With a sequenced protocol, the task is less overwhelm- ing, and we all feel comfortable adapting to the changing winds.

Undercutting kills you and your competition— but you die first

For sixteen years, my family held the same booth at our farmers market. There were typically two other meat producers in attendance. Every few years, we would see some new farmers enter the market with overlap- ping products. And every time, we’d see the price wars begin, with a renewed race to the bottom. The customers got some fabulously cheap prices. And then one or two farmers would go out of business. The lowest-priced producers are almost always the first to go. They sell out of product, get a powerful sense of exhilaration for having the longest lines, pat themselves on the back for being genius marketers, then run out of stuff to bring for the following week . . . and run out of cash before they can pay all their bills. Undercutting the competition does not make you a more creative, savvier, or more honorable business- person. It just hurts your bottom line and trains the customer base to undervalue your (and your competitors’) hard labor. And that means the life-serving economy is endangered by your practices. Because if the businesses aren’t viable, then they don’t stick around, having the powerful economic, social, and ecological impact that we need from them.

Your time and emotional investment are legitimate expenses

The year I published Radical Homemakers was the worst year of my life. I had two small children. I was homeschooling and working in the fam- ily business. All day long my phone was ringing with reporters. Emails constantly pinged in. And I was abandoning my kids and running out every week to speaking engagements. Some of those engagements were crowded with eager listeners. Some of them had only one or two weir- dos who came in off the street hoping for free cookies. And every time I left home and farm, I had to find ways to keep my kids educated and fed, and keep the business running, and stave off my exhaustion. I suf- fered chronic stomachaches and countless stress-related health issues. My digestion was so disrupted that I had to subsist on a diet of bone broth and tea. At my wits’ end, I called my friend Joel Salatin, a long- time leader in the sustainable farming movement and popular speaker. I did my best to keep my voice calm, hoping he wouldn’t hear the tears I was choking down. Joel listened attentively to my woes, then had one easy, simple solution.

“Charge more,” he said. “Double your price. And if your life doesn’t get more balanced, then triple it. If you’re feeling this kind of stress, then you aren’t valuing the work you’re currently doing.” He was right. By making time for everyone who requested it, I was brush- ing off my kids’ education and my personal well-being. And when I considered the value of my nonmonetary income and how much of it was getting lost to saying yes to every request, that was an exorbitant price to pay. I learned to respond to emails once or twice per day. I accepted interviews between the hours of 1:00 pm and 4:00 pm only two days per week. And I nearly quadrupled my speaking fee. The result? I lost a lot of speaking gigs. But I recovered my nonmonetary income. The number of my speaking engagements fell to only a few times per year, and the organizations that came up with the funds had a greater investment in the success of the event: they worked harder on publicity. And now when my family packs me off on a speaking gig, they’re fully invested, too. Sometimes people ask me how I come up with the figures that I charge, and the answer is simple: “It’s the price I need to not be resentful that I’m away from home.”

The right price reduces waste and increases value

I saw this straightaway with my public speaking work. True, I had fewer gigs. But the venues I accepted had much greater attendance—and the people who came were there to hear me. I reached just as many people, with a lot fewer freeloading cookie munchers.

When it came to selling meat, I saw something similar. Americans have a callous attitude of entitlement about our food. Our food waste in this country is estimated at about 40 percent.3 We have a sickening habit of leaving scraps on our plates to be sent to the landfill to gener- ate methane and letting leftovers spoil in our refrigerators. Or we don’t make the time to cook food properly, much less sit around the table to enjoy and celebrate it as we should. Food not tasted is also wasted.

When a customer spends twenty-five dollars fora single rib eye steak, something changes. They recognize it as a privilege rather than an entitlement. They let me teach them how to prepare it properly. They make time in the kitchen for it. They savor each morsel and teach their family members to do the same. They eat the fat, recognizing its importance in improving satiety and providing the fat-soluble vitamins. They add the bone to a bone collection in the freezer, to be boiled into broth at a later date. They save meat and vegetable scraps for broth-based soups. They consume more wisely and value each purchase more fully.

The right price improves your customer base

The first year Bob and I saw major competition at our farmers market, I panicked. Their prices were 25 to 30 percent lower than ours, and I didn’t know how we were going to survive the season (much less how these other farmers could make ends meet). I focused on improving my sales pitch to retain our customers. Bob had a better idea.

The first time a customer chastised us for being more expensive than our competition, his gentle brown eyes widened with empathetic sincerity. “You know,” he said. “I think the other farmers are going to do a better job meeting your needs.” And he let them walk away. The customer waiting next in line watched the entire display. Rolling her eyes at the first customer’s rudeness, she opened her wallet, paid us our asking price, and thanked us for being there. So did the next one.

Following Bob’s lead, I began screening customers. If they greeted us with hostility and didn’t want to pay the price we needed to survive, we didn’t want to invest our valuable sales time trying to capture their business. We lost our worst customers that year and discovered that we pruned our business back to the best of the best. The customers we

retained honored our labors. We were less harried at our booth, and we were able to give our quality customers the time, service, and attention they deserved. Happy, satisfied customers brought us new happy, satisfied customers. We pruned back only to enjoy renewed growth.

Agnes is probably my favorite example of a valuable customer loss. Every time she came to buy, she scarfed down our free samples, chewed without closing her mouth, and sniped at us about our prices while blowing crumbs and bits of food across our sales counter. While she may have simply been trying to look out for her own pocketbook, she was telling us with every visit that we didn’t deserve our livelihood. If we listened to that kind of toxicity long enough, we’d have been out of business. And Agnes the artist could have watched a gated community replace our picturesque mountain farm. By eliminating the Agneses from our customer base, everyone’s experience improved. And even Agnes gets to benefit from the pruning. Our quality of business life improved, increasing the sustainability of our farm. That means Agnes doesn’t eat our products, but she benefits from our protection of her local watershed, our carbon sequestration, our property taxes, and our contribution to the local economy. Some customers are truly worth losing, and fair pricing can be an efficient way of shedding them.

If the price isn’t working, promotions are always an option

If a price isn’t right, it can always be changed. And you can even turn that adjustment into a marketing opportunity. Offering a special promotion gives you news for your email newsletter and something interesting to post to your social media accounts. It often results in additional sales of other products, and it might even bring a new customer in your door to try your product.

So that’s all. That’s what I can tell you about pricing — that customers’ outrage isn’t actually about you, that we can choose to wear a Cloak of shame or toss it aside and hold our heads high to ask for what we need, and that good pricing makes our business stronger by increasing our gross income, reducing waste, and even improving our customer base. And if not, well, I guarantee that you’ll definitely get a good story to share no matter what happens!

Is all this discussion hitting a nerve with you? I hope so. If you’re like me, you’re forever on a quest to live more deeply, make time for what matters and still keep the bills paid. So Be sure to check out my new book, Redefining Rich: Achieving True Wealth with Small Business, Side Hustles and Smart Living, where I talk about the balance between being creative & recognizing the riches right under your nose…I also give a lot of helpful advice about money and small business. Don’t miss it!

This podcast happens with the support of my patrons on Patreon. And this week I’d like to send a shout out to my patrons Leslie Hempling & Leighanne Saltsman.

Thank you, folks! I couldn’t do it without you! If you’d like to help support my work, you can do so for as little as $1/month by hopping over to Patreon and looking up Shannon Hayes.

Setting prices really is an art, isn’t it? I’m a freelancer myself, and I’ve gone through that same process you did. I used to be so nervous about quoting a worthwhile price to people who inquired about my services; I was afraid that I would scare off clients and end up with none. But I realized that I was starting to feel resentful about doing hard work at relatively low fees, so I started quoting higher. The same thing happened – I did lose some clients. However, I was so motivated to work for the ones who accepted my fees – I made sure I did excellent work so that they got their money’s worth. Thank you for sharing this wonderful post!